Fatoumata Seck

I didn’t want an important part of my PhD work to be done by someone else because I wasn’t a bioinformatician.

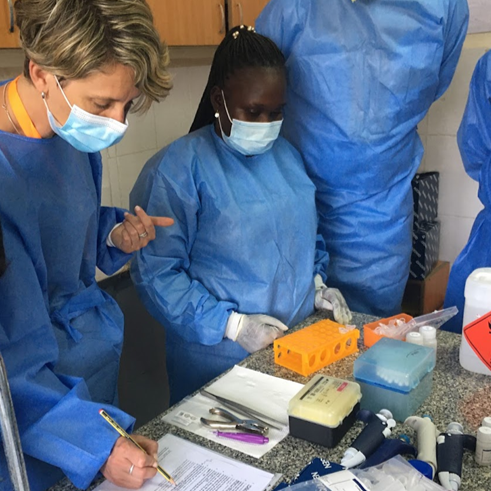

As a PhD student registered at the African Centre of Excellence for Biotechnical Innovations for the Elimination of Vector-borne Diseases (CEA/ITECH-MTV) and a fellow of the West African Network of African Centers of Excellence (ACEs) on infectious diseases (WANIDA), Fatoumata Seck is currently completing her PhD work at the Institut Pasteur de Dakar (IPD) in Senegal. She is part of a malaria vector control project led by Dr Benoit Assogba from the Medical Research Council Unit The Gambia (MRCG) at LSHTM, which aims to test the use of specially designed chemicals called small molecular inhibitors as an innovative approach to control malaria mosquitoes.

“Following the investigation of the molecular and genetic factors driving malaria vector fertility and competency, we’re aiming to target specific genes that are important to the reproduction of mosquitoes and their ability to transmit Plasmodium parasites to humans,” she explains. This involves synthesising specific small molecules targeting these genes to disrupt their function in the mosquito, which could potentially reduce the density of mosquitoes and thus decrease malaria transmission.

This method is under investigation and needs to be tested in the lab before it can be implemented. That’s where genomics is vital.

“Before going into the field to apply this [mosquito control] tool, we need to have adequate information about those genes in natural populations,” she explains. “Thanks to the MalariaGEN Ag1000G project, we have thousands of Anopheles genomes to analyse and get information from.”

Over the course of Fatoumata’s budding career in malaria research, she has already picked up an interesting range of knowledge from various institutions. After pursuing her studies at the University Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar and a master’s internship in medical entomology at the Institut Pasteur de Dakar, her journey into malaria genomics began as a PhD student in entomology at MRCG. There, she realised that she was missing the skills needed to analyse the genetic diversity of the potential target genes for the malaria vector control project.

“I didn’t want an important part of my PhD work to be done by someone else because I wasn’t a bioinformatician.”

She was determined to learn the basic data analysis skills she needed to understand the data from Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes and further interpret the results. She credits the strong support she received from her colleagues at MRCG and IPD to complete this objective of her PhD. “I couldn’t thank them enough for being patient with me, especially my supervisors Dr Benoit Assogba from MRCG and Dr Ibrahima Dia from IPD.”

Once she mastered the basics, an exciting opportunity to go into further depth presented itself – she was selected to be among the 50 participants of the first cohort of the MalariaGEN-PAMCA Vector data analysis training course in 2022.

After completing the training course and attending two hackathons at PAMCA conferences, Fatoumata will now share her skills with new participants of the upcoming third cohort of the training course.

“In the first cohort, we were trained to also be able to train others. [Going] from a student to a teaching assistant will be a way for me to test my knowledge and improve myself, since by teaching, I will be learning too.”

She also emphasised the importance of self-belief, mentorship, and seeking advice and guidance from those with more experience.

“When I got the email about becoming a teaching assistant, I thought it might be a mistake because I am still learning.” Now, she says the training course has become one of the avenues through which she is building both her skills and confidence.

“Thanks to the trainers and everyone from the team for their availability and engagement!”

Fatoumata is also a mentee under the PAMCA Women in Vector Control Mentorship Program “LiftHer2”, a platform dedicated to fostering women’s leadership, capacity building, self-confidence, and networking. With the guidance of experienced women in the vector control space, mentees are empowered to design, lead, and implement effective control interventions for malaria and other vector-borne diseases.

“I know that mentorship is very important when you are doing research,” she acknowledges. “Malaria is a very integrated field and having broader knowledge will help you understand it more and make good decisions.”

Valentina Mangano

At the end of the day, the goal is to provide accessible tools for meaningful interpretation of surveillance data.

Dr. Valentina Mangano is an Associate Professor of Parasitology at the Department of Translational Research and New Technologies in Medicine and Surgery at the University of Pisa in Italy. Her current work revolves around an impactful two-pronged project to enhance malaria diagnosis and surveillance in South Sudan.

This initiative, funded by the Global Fund through the Italian Agency for Cooperation and Development, integrates operational research into a programme coordinated by the NGO Doctors with Africa CUAMM. It aims to strengthen malaria diagnostic, preventive, and curative services at the various levels of the healthcare system in the state of Western Equatoria in South Sudan. Valentina leads a malaria parasite study that intertwines with the efforts of the NGO, with the goal of improving malaria diagnostics and surveillance through capacity building and molecular epidemiology activities.

“The idea is to generate very strong evidence needed to make decisions for malaria control, but also at the same time, to build capacity in that area,” she says, summarising the overall goal of the study.

To this end, the first phase of the programme has been filling existing gaps in the healthcare facilities in the region by equipping labs with the necessary equipment for rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) and microscopy. “We also provided training for clinical and laboratory personnel in diagnostics and molecular surveillance methods,” she explains.

The operational research ties in with routine healthcare activities, so it enables the team to collect malaria parasite samples regularly. Here, she recognised that these samples could be used for malaria molecular surveillance, and she sought to fill this gap by collaborating with MalariaGEN. “While writing up the project, I proposed collaborating with MalariaGEN for parasite molecular surveillance,” she recounts. “There was a clear need for deeper insights into parasite dynamics and drug resistance patterns.”

Sequencing the parasite samples collected from these healthcare settings will generate epidemiological knowledge into parasite species, drug resistance, and diagnosis escape which can support informed decision-making. The data will also feed into the next MalariaGEN parasite data resource so that National Malaria Control Programmes and other public health actors can use it to adapt their prevention and control strategies.

The preliminary data from their efforts are already shedding light on malaria parasites in the Western Equatoria state. “We’ve received about four-fifths of the molecular surveillance data [on malaria parasites], and we found evidence of drug resistance, particularly to artemisinin and partner drugs, as well as to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine.”

Crucially, there have been reports of resistance to the widely used antimalarial artemisinin and genetic mutations linked with diagnostic test failure in other East African countries bordering South Sudan. This data is therefore very important for South Sudanese public health officials. “The data is not complete, but it’s the first generated evidence that is available so far for the Ministry of Health to start recognising the problem of drug resistance in the country,” she adds.

Valentina believes the next leg of the journey is to facilitate public health actors to interpret the data from the study.

“Along with our partners, we are looking into developing a simple toolkit for data analysis,” she says, recognising that this would be essential for public health officers to make informed decisions. “At the end of the day, the goal is to provide accessible tools for meaningful interpretation of surveillance data.”

She also underscores the pivotal role of capacity-building activities as an essential pillar in the battle against malaria.

“I think for me, it’s important to work on these different aspects because you need capacity building at every level, on both diagnostics and molecular surveillance.”

Damaris Matoke-Muhia

Whatever decisions women make at higher levels will not only be because of the knowledge they have received through training, but also because of the experience they have had as mothers, as sisters, as women in the community.

Dr Damaris Matoke-Muhia is a biomedical scientist and a Programme Manager for Capacity Building, Gender Mainstreaming, and Career Progression at the Pan-African Malaria Control Association (PAMCA). As a dedicated advocate for gender equality in science, she sheds light on this missing piece of the puzzle.

PAMCA Women in Vector Control (WiVC) was born out of a critical observation made during PAMCA annual meetings: a glaring lack of female representation in pivotal roles within vector control activities.

“Most of the time, if you looked at the panellists, keynote speakers, and symposia organisers, you’ll find that it was heavily reliant on mostly the male gender,” Damaris explains.

In fact, a 2018 survey on women’s representation in vector control activities like entomology showed only about 20 women for every 100 people. For the activities to be effective, this imbalance had to be rectified.

Damaris also points out that women are underrepresented in leadership and decision-making roles within malaria research – most women are co-investigators rather than leads in proposals and projects.

“We felt that there was the need to look at how we could bridge that gap.” Damaris remarks that it was time to think about how to bring all voices on board in addressing the control of vector-borne diseases, including the most deadly of all, malaria.

With a chapter in over 30 African countries, PAMCA WiVC is working on a number of initiatives to increase the participation of women in the control of vector-borne diseases. For example, “LiftHer2” is the second iteration of the WiVC’s mentorship programme which matches early-career women working in vector-borne disease control in Africa with more experienced counterparts.

“We want to mentor women in this field to occupy decision-making positions… so that whatever decision they make at higher levels will not only be because of the knowledge they have received through [scientific] training, but also because of the experience they have had as mothers, as sisters, as women in the community.”

Damaris also proposes that women’s experience at the community level, where they often take the lead in ensuring family health, plays into vector-control activities. “We also want to engage non-professionals, who are the women at community levels, school-going children, and the local elders, to educate and sensitise them of the need to use the interventions effectively.”

WiVC’s impact extends beyond individual empowerment to systemic change. Damaris highlights the importance of advocating for gender-sensitive policies and creating safe work environments for women in vector control.

“We are looking at engaging institutions across the continent to create safeguarding policies and anonymous reporting structures to enhance workplace safety and prevent harassment, bullying, or discrimination from happening.”

To truly achieve gender equity in vector control, men also need to be part of the cause, and this is an idea that PAMCA WiVC is actively reinforcing. “We do not only engage women. We need men as allies, especially to promote equal participation and leadership opportunities.”

Ultimately, Damaris drives home one key message – to rid the world of malaria and other vector-borne diseases, we need to build an inclusive and equitable workforce.